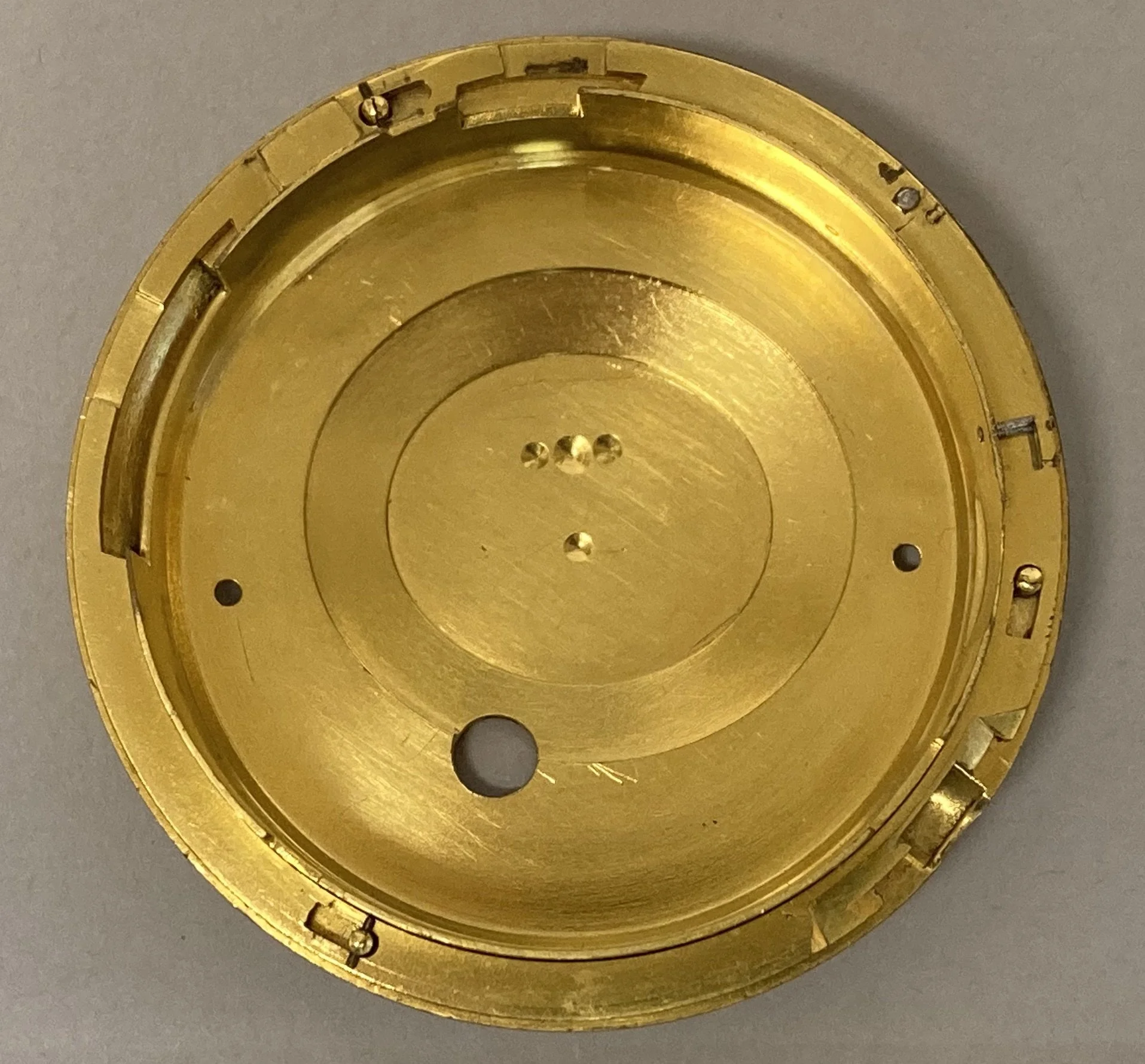

Josiah Emery No. 1107

This large pocket watch in gold consular case, with regulator-style enamel dial, signed ‘Josiah Emery Charing Croƒs London 1197’ on the dustcap and potence plate, is one of only 23 surviving Emery lever watches, having his 2-plane lever in straight line arrangement. The craftsmanship of the watch is exquisite, all the train pivots are jewelled including the fusee, and the movement also incorporates Stogden-type half-quarter dumb repeating.

The earliest form of the lever escapement was developed by Thomas Mudge in the third quarter of the 18th Century, but he only made three or four watches/clocks incorporating this experimental escapement. Emery modified the design somewhat and produced approximately 38 high-quality, well-performing watches with the escapement, bringing it to a wider international audience and proving it was possible to produce well in higher numbers than Mudge’s early experimentation allowed.

The lever escapement was to see some more modification and refinement in the years to come, but ultimately would remain close enough in design and principle to still be considered the same escapement as Mudge’s and Emery’s early work. The lever reached widespread use in both watches and carriage clock platform escapements in the 19th century, and continues to be the most commonly used form of watch escapement in modern mechanical wristwatches.

As the forerunner to the modern lever escapement, all of the surviving Emery Levers are of substantial cultural value. As arguably the best, most complete, most original- condition of those 23, the significance of this particular watch, the technology contained within it and the craftsmanship it represents, cannot be overstated.

For a full discussion of the historical context and description of most of the other Emery Levers, see: Betts, J. ‘Josiah Emery (Parts 1, 2, 3, 4 & 5)’ in Antiquarian Horology Vol. 22, Nos. 5 & 6, and Vol. 23, Nos. 1, 2 & 3. (March 1996, June 1996, September 1996, December 1996 & March 1997).

A previous inspection had established the presence of multiple areas of localised steelwork corrosion. The watch is considered too historically significant to be run, as this would risk permanent loss through wear and tear, so this conservation project was initiated to remove all active corrosion and stabilise the watch for storage. Upon disassembly, multiple sites of steel corrosion were discovered, as well as small areas of corrosion to two brass components.

The areas of corrosion were removed under high level magnification, working through customised scrapers of successive hardness, starting with pegwood, followed by porcupine quills and mother of pearl, and resorting to burnished steel picks and scalpel blades where necessary. After cleaning, every treated component underwent a two-stage chemical drying process to draw out any remaining moisture.

Some of the areas of corrosion had progressed to very deep pits which necessarily left those areas with quite scarred/pockmarked surfaces at the loss sites after the corrosion was removed. To refinish those areas for aesthetic purposes would have been impossible without interfering with the surrounding areas of original finish, and consequently it was decided that no refinishing should take place in order to preserve as much of the original finish as possible. This sacrifices some small areas of aesthetic value in favour of preserving historic craftsmanship.

Finally, the jewel holes were pegged out, and the watch was reassembled without lubrication to prevent any potential corrosion problems that could be caused by the breakdown and acidification of lubricant. The watch was left unwound with minimal set-up on the mainspring, enough just to hold the fusee chain in place. A custom brass set-up key was made to fit the set-up worm, and this was returned in the box with the watch.

This project was carried out in conjunction with Malcolm Archer FBHI, and coordinated by Su Fullwood. All images and information is shared by kind courtesy of the Trustees of the Goodwood Collection.

Watch image gallery

Delicate components such as hands were fixed to brass blocks with temporary conservation adhesive (Paraloid B72) to allow them to be worked on without risk of bending/snapping. (Photo by Su Fullwood)

Custom brass collets were made to facilitate the secure holding of screws without risking damage to the threads.

The balance spring stud cock screw was one of the most significantly corroded components.

The watch fully reassembled after treatment, showing the balance spring stud cock screw in situ - approximately 50% of the historic finish and blueing of the component has been saved.

treatment image gallery